Ed Note: This article is extremely long, so feel free to make use of the table of contents to jump around or to read in chunks. For those interested only in a summary, skip to the conclusion.

Misinformation and conspiracy theories have become endemic to the online ecosystem in recent years. They can be political, like the claim that Russia rigged the 2016 election for Donald Trump or the reverse claim that Joe Biden stole the 2020 election from Donald Trump. They can be medical, like the claim that COVID-19 vaccines cause your heart to explode or that COVID-19 itself was some kind of Chinese bioweapon. They can even be insane, like the claim that chemicals in the water can “turn the friggin’ frogs gay” or that Jews start wildfires with space lasers.

But ever since Israel responded to the attacks on 7 October 2023 with a campaign so brutal and destructive that international bodies have repeatedly labeled it a genocide, a new mind virus has entered the body politic. This misinformation has been manufactured with laser-like precision to appeal to the sentiments of left-wing and progressive elements in the Western world. With the Western left devastated intellectually and organizationally by decades in the political wilderness, many of them have begun to believe it. It’s difficult to blame them. They have, after all, watched in abject horror as Israel has slaughtered over 35,000 people (15,000 of them children) and left all of Gaza on the brink of starvation. In ground this fertile, the myth has permeated left-wing spaces with shocking speed. Those who have paid attention to internet discourse have likely encountered it and may even believe it.

Americans are the most vulnerable of all, having lived lives largely untouched by mass violence and devoid of any meaningful political education. The idea that Israel can exact such an obscene humanitarian toll with total impunity — not just tolerated but actively supported by Western governments — is unimaginable to most. The myth also relies heavily on memories of being lied to about the Iraq War and general distrust of the media. Under these conditions, many leftists and progressives (especially in the Anglosphere) have proven uniquely vulnerable to the vulgar materialism of what this article will call “the gas-driven genocide myth,” which centers oil and gas as the cause of the current ethnic cleansing in Gaza.

It’s a compelling narrative. It has many stripes of believer and has taken on many flavors across the internet. If the online mythology could be distilled into its purest essence, it would be this: Palestine — the occupied nation that rightfully consists of the entire territory of historic Palestine — has hundreds of billions of dollars of oil and natural gas reserves. These natural resources are the real impetus behind Israeli colonization and especially the recent war in Gaza, as they have been for colonial and imperial endeavors everywhere. The whole bloody history of Israel-Palestine is nothing more than a smokescreen intended to disguise a land/resource grab. Seizing these energy reserves — a longtime goal of Israel and their Western backers — has finally become possible after the 7 October attacks gave them an opening. The United States and EU are not merely allies of Israel but conscious backers (and perhaps even orchestrators) of genocide in the name of fossil fuels.

Not a single part of this narrative is true.

Table of Contents

How the sausage was made

The claim that the current war in Gaza is about oil and natural gas poses an obvious question: what oil and natural gas? Israel-Palestine is, after all, famously “the one place in the Middle East without oil.” If there is a credible source that suggests that oil and gas really are present, then it is necessarily the most important one for this myth. Luckily for those wishing to refute the myth, there is a single point of origin for virtually all of the claims about Palestinian oil and natural gas.

The source in question is a document from August 2019 called “The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: The Unrealized Oil and Natural Gas Potential.” It was authored by a subsidiary organization of the UN called the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (UNCTAD) UNCTAD is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1964 with the intent of, in their own words, “support[ing] developing countries [in accessing] the benefits of a globalized economy more fairly and effectively… as vehicles for inclusive and sustainable development.” In practice, they publish reports suggesting how poor postcolonial nations can get in on global trade with resource extraction and low-end industrial production, theoretically to the benefit of all. The “Conference on Trade and Development” is neither a decolonial radical publishing house nor a neutral statistical reporting office. They are a business-facing organization, and they act like it.

That 2019 report on Palestine was the fifth such report that UNCTAD had written. In the aftermath of the Second Gaza War in 2014, the UN General Assembly requested that UNCTAD write a series of reports on the economic impacts of the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian people. Each one built on the previous documents sequentially, adding new analytical dimensions to calculating the cost of Israeli occupation while summarizing previous ones. The 2019 report in particular chose to discuss the region’s oil and natural gas resources, which had been circulating through academia and receiving a lot of news coverage at the time. That’s why only the last two of the report’s six chapters are actually devoted to oil and gas. The four previous chapters cover the objectives of the study, the subject matter of the past reports, and the legal and economic justifications on which the analysis is based.

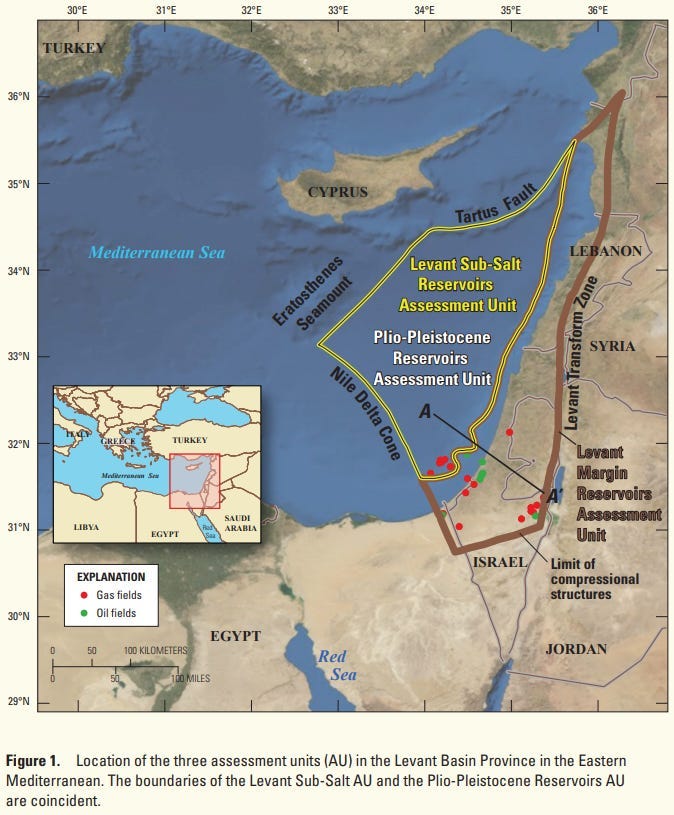

The first problem was that it was not this background information about the report that went viral, but the big numbers in the executive summary. The massive figure of $524 billion in energy reserves can be accessed even without downloading the report, so it’s fairly easy to see where the claims came from. The very first sentence claims that “the Occupied Palestinian territory lies above sizeable reservoirs of oil and natural gas wealth,” and if one were to say, skim the rest of the text and look for numbers to attach to that sentence, the only numbers of any kind in the summary would jump out: “122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas at a net value of $453 billion (in 2017 prices) and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil at a net value of about $71 billion.”

Now, to be fair to the myth-mongers, these are real numbers. To quote the executive summary at slightly greater length:

“…the Occupied Palestinian territory lies above sizeable reservoirs of oil and natural gas wealth, in area C of the occupied West Bank and the Mediterranean coast off the Gaza Strip… The new discoveries of oil and natural gas in the Levant Basin, amounting to 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas at a net value of $453 billion (in 2017 prices) and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil at a new value of about $71 billion…”

-pg. v

A little bit of math will demonstrate that $453 billion + $71 billion is $524 billion, the figure constantly attached to the myth on social media. On some level, this should be comforting. At least those numbers are real.

Unfortunately, this is a deliberately misleading quotation. The two passages quoted above, conveniently bridged by those little ellipses, are separated by an entire page of content. Those two segments reference two different regions. The Levant Basin is a region that includes Palestine, not just another term for Palestine. Any read closer than bare-minimum skimming would immediately reveal this information. The numbers the report ascribes to the energy reserves of the Occupied Palestinian territory are more than an order of magnitude smaller than the numbers provided above.

None of that stopped the deluge of smug, astonishingly self-confident hucksters — many of whom did not even bother distinguishing between Palestine, Israel, and the Levant Basin as a whole — from shouting the $524 billion figure from the rooftops. The sheer speed with which the gaseous genocide narrative spread is almost as breathtaking as the scope of its penetration. The so-called journalists of the anti-imperialist blogosphere believed it, of course. They were already arguing that Israel was going to genocide Gaza to take their gas during both the 2008 Gaza War and the 2014 War. But the surge in anti-Zionist sentiment coupled with the receptive global audience of uninformed Westerners on Wild West social media platforms like Twitter and TikTok caused it to go viral. It is now such a widespread belief that its merits are no longer even up for discussion in many “anti-imperialist” circles.

The person most responsible for the current iteration of the gaseous genocide myth appears to be Richard Medhurst, the British-Syrian “journalist” responsible for so much misinformation on so many topics that these authors regularly refer to him in private as “the usual suspect.” His meandering, historically illiterate conspiracy theory (published on Twitter on 26 October) touches on almost every single one of the standbys that would go on to take anti-Zionist social media by storm in the following weeks: the Netanyahu visit to the UN about the “new Middle East,” the New Silk Road nonsense, the connection to the war in Ukraine and Russian gas exports, the Leviathan gas field, Lebanon’s Karish gas field, and Gaza Marine. The only thing missing from it was the UNCTAD report as a source.

To be fair, some people were making the connection prior to Medhurst. One of them was infamous anti-vaxxer and “Stop the Steal” activist Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai, who (incorrectly) cited UNCTAD’s figures to make the case. He also claims to have invented email at age 14. But outside of small accounts plagiarizing obscure foreign policy blogs, Medhurst appears to have been the first person talking about this to a large audience. His first video on the topic would go on to accrue 1.8 million views.

Medhurst’s video set off a domino effect that rocked anti-imperialist social media over the following days and weeks. The very next day, former UFC/MMA world champion and terminally online anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist Jake Shields tweeted that Israel was committing genocide in Gaza to seize the “massive amounts of oil” there. The day after that, French “independent researcher” Freddie Ponton published a Twitter thread repeating an Al Jazeera article almost verbatim that was using the UNCTAD report as a source. From here, the report then sprang into the public discourse. It popped up again soon after on the Substack newsletter Planet: Critical, written by “climate corruption journalist” (her description) Rachel Donald.

Another key inflection point was reached when the information percolated to TikTok. Two directly linked videos came out on that platform on 31 October and 1 November which amplified the key tenets of the gaseous genocide myth and the accompanying Ben Gurion canal nonsense (which these authors intend to cover in its own article). First, on 31 October, 25-year-old small-time Emirati beauty influencer Celine Lilas published a TikTok video of Wikipedia-level research about the Suez Canal arguing that Israel wanted to depopulate Gaza to build the (imaginary) competing Ben Gurion Canal. She somehow managed to do this without addressing a single historical event between 1979 and 2021. It went on to accrue over 4 million views on an account that had previously averaged fewer than 10k views per video. The following day, self-described “twentysomething Egyptian Millennial” and dentist Hacen Sol published his own TikTok video in response which agreed with Lilas’s points and then discussed the Gaza Marine gas field at length before asserting that Israel was bombing Gaza to prevent them from exploiting the field. He also likely coined the phrase that would soon be everywhere: “It was never about Hamas.” His video received over 500k views on an account that had been even smaller than Lilas’s.

With its stakes firmly in the ground, the myth rippled out from its points of origin. Medhurst put up the second part of his video on Gaza — also covering the Ben Gurion canal — later that day on 1 November, where it would gain another 1.1 million views. When the small communist Twitter account “MassStrikeNow” tweeted a meme two days later that claimed that “there is $524 billion worth of oil reserves in Palestine that Israel is trying to use this opportunity to take,” the response was overwhelmingly positive. The meme received over 1.5 million views and tens of thousands of quotes and retweets, the overwhelming majority of whom either invoked the Ben Gurion canal or provided the UNCTAD report as a source. The narrative had already reached critical mass. Twitter accounts were claiming that Palestine had “hundreds of billions of dollars” in oil reserves left and right later that same day. They also, predictably, cited either the UNCTAD report or Medhurst as their source.

Shortly thereafter, the myth moved on completely from the innovators and into the hands of the content repackaging machine. On or shortly before 8 November, famously reliable news organization Russia Today (now RT) ran a segment with Saskia Taylor called “Gaslighting Gaza,” which synthesized the claim that Palestine possessed “over $453 billion of natural resources” and citation of the UNCTAD report with nonsensical geopolitical analysis almost identical to Medhurst’s work on Twitter. (Not quite cease-and-desist territory, but close.) The segment can still be found on Twitter. That same day, infographic account “feminiiista” published their piece on Gazan gas on Instagram, after which the myth began to circulate there as well. The day after that, fringe “news media channel” run by Australian Muslim rights advocate and pro-Pakistan super soldier CJ Werleman released a video that synthesized the work of a number of bit players into one slick production for his 250k subscribers. The myth was no longer merely circulating. It had begun solidifying.

From the middle of November on, the myth no longer substantially changed but was merely repeated ad nauseum for new audiences. 14 November saw it enter the anti-imperialist blogosphere in force when accountant and activist Betsey Piette wrote two identical pieces on the matter for the Worker’s World and the “International Action Center.” An op-ed published the next day in Middle East Eye lent it a veneer of traditional news credibility, as did a second one a few months later. Al Jazeera fulfilled the same function, although theirs came well before and well after. Graphic journalist, CSU Long Beach undergraduate, and “associate producer of Insights” at Atlas News Luke Wines created a short video that accrued over 1.5 million views and over 120,000 likes on Instagram. While it avoided outright connecting gas to the ongoing war in Gaza, the video described Gaza Marine using virtually identical terms to other myth-mongers and compared the current conflict to the Iraq War, which it described as an effort by the US to seize Iraqi oil.

And, of course, deranged Minnesota-based pro-Assad rag MintPress News has been on the warpath about the issue without pause. Held back only by the small size of their audience, the news org that local paper MinnPost once called a “publicity mill” has published a barrage of social media posts and articles about the issue. These posts have followed the typical MintPress behavioral model of attaching themselves to “hot” topics and self-promoting relentlessly, all the while carefully avoiding ever citing a source. This is true even when they obviously plagiarize other news sources, such as this post which ripped off this Reuters article from the previous day, or how everything posted on gas in Gaza since November 2023 has copied details from the UNCTAD report without citing it.

Virtually all of these sources were using the 2019 UNCTAD report as a source, either openly or through regurgitated factoids transmitted by the social media mind virus. In the face of this virality, the tangible facts of the report turned to undifferentiated sludge. Before the seething mind-webs of the internet, oil became gas and gas became oil while numbers ran like water. Distance folded and 20 miles became indistinguishable from 200. Trillions of cubic feet of gas and billions of barrels of oil accumulated and multiplied in the unseen dark. And all the while the report was twisted in ways that its authors probably never even imagined, let alone intended. To put it mildly, there is a clear pattern of misrepresenting the facts of the report. It makes sense, then, that before further breaking down the problems with this narrative the things that UNCTAD actually said should be examined in depth.

Conferring on Trade and Development

Nowhere does the UNCTAD report claim that Palestine has $524 billion of energy resources, let alone Gaza specifically. In fact, it doesn’t claim that Gaza itself has any such resources at all. The report makes two separate but interlinked arguments: first, that “Occupied Palestine” has oil and gas it is being prevented from exploiting, and second that the whole Levant Basin region has tons of oil and gas resources which would be shared under ideal conditions. This is befitting of the two distinct regions under discussion. (Although obviously Palestine is part of the Levant Basin.)

First is the argument on “Occupied Palestine,” a phrase which demands clarification. Left-wingers in general have a bad habit of assuming that terminology is used identically by all parties involved, which leads to confused and unproductive discourse. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between the way many left-wingers and progressives use the term and the way that the UN uses it.

It has, for decades, been a fact taken for granted by the vast majority in progressive and left-wing circles that the very existence of Israel constitutes a territorial violation of Palestine. More specifically, a direct comparison is drawn between Israel and the dispossession of Indigenous people in the United States, which would make both societies “settler societies” engaged in what scholars call “settler colonialism.” It is common to see American leftists and progressives alike refer to locations in the US as “occupied land” rightfully belonging to an indigenous people. By the same token, leftists and progressives regularly refer to land in what international law would recognize as both Israel and Palestine (i.e. historic Palestine) as “occupied Palestine.”

When the UN discusses “Occupied Palestine,” they mean something much more specific. Authors for the UN and its subsidiary organizations are expected to ground their judgements in international law, which recognizes two nations in historic Palestine: Israel and Palestine. The borders of these nations are recognized based on the 1949 “Green Line” borders, which designates Palestine as the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. However, as those schooled in the region’s history are aware, Israel has occupied much of the West Bank and de facto occupied Gaza through its maritime blockade. This distinction is made abundantly clear by the 2019 UNCTAD report.

The second chapter of the report, titled “The legal framework: Historical precedents,” is devoted to this question and to defining “occupation” in this context. In that chapter, the Secretariat describes the constraints on occupying powers according to international law, which are governed by the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention. Failing to behave in accordance with those laws by, say, preventing Palestine from developing its natural resources, imposes “real and opportunity costs on Palestinians” (pg. 3) that can have monetary value assigned. After clarifying that occupiers are forbidden from exploiting natural resources under international law, the report states that:

“Israel’s status in the Occupied Palestinian Territory is considered that of a belligerent occupant. [ed note: That is, as a foreign power occupying another country’s land during wartime] The Security Council of the United Nations, as reflected in its resolution 446, regards the Fourth Geneva Convention as applicable to the territories occupied by Israel in 1967… This conclusion is not disputed by the Supreme Court of Israel. It also considers Israel’s status in the Occupied Palestinian Territory to be that of a belligerent occupant.”

(-pg. 4, emphasis added)

The emphasized segment is the UN’s definition of the “Occupied Palestinian Territory.” They also explicitly define which territories are considered those “occupied in 1967.” On page 18 of the report, the Secretariat states that “following the occupation by Israel of Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, in 1967, control of land, natural resources, and water has been at the [center] of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” (emphasis added). There can be no doubt that the 2019 UNCTAD report hews to the standard UN definition of “Occupied Palestine.”

With that clarification laboriously made, it is time to discuss what the report says about these occupied territories and their resources. The Secretariat centers two key natural resource nodes in their discussion: the Gaza Marine gas fields located off the coast of the titular strip and the Meged oil fields located in/around Area C of the West Bank. The former is an undeveloped resource discovered in 1999 which has yet to be exploited. Israel has used its “last say” legal rights to permit or block maritime activity due to security concerns — rights which were given to it by the same international agreement that gave Gaza Marine to Gaza in the first place — to prevent development of the site. For their part, Western energy concerns have largely steered clear of the whole situation. The Meged oil field, on the other hand, is located right at the edge of the West Bank’s border with Israel. Most of the field is physically within the West Bank (and thus legally Palestinian territory), but it is within Area C, the portion that makes up most of the West Bank and which is under Israeli control.

Much more attention is devoted to Gaza Marine than the Meged, which seems sensible. The report suggests that based on average natural gas prices and a favorable development schedule: “Palestinians have already [ed note: as of 2019] lost roughly $2.570 billion through prevention of the exercise of their right to benefit from the exploitation of their natural resources” (pg. 26). That’s a lot of money, especially for a critically impoverished place like Gaza. Even if those figures are taken with appropriate skepticism (and there are many reasons to do so), such a revenue stream could have made a real, tangible difference for millions of Palestinians.

Much less is said about the Meged oil field. The size of the field’s total estimated reserves (~1.5 billion barrels) is declared, their value is assessed, and that valuation combined with the same interest rate considerations as the Gaza Marine fields is used to provide a final figure of $67.9 billion worth of losses to the West Bank. It is unclear why this figure does not account for extraction time the way that the Gaza Marine estimate does, but if the figures provided are correct then the losses accrued by Israeli occupation of Area C of the West Bank are staggering.

An illuminating example of the restraint of the United Nations in discussing Occupied versus Historical Palestine comes when they describe the oil and gas resources located offshore in Israel’s Exclusive Economic Zone. This is territory that, per the United Nations 1984 Convention on the Law of the Sea, is territory whose natural resources are the sole right of Israel to exploit as long as it is within a certain distance of the Israeli coastline. When discussing those resources, the Secretariat says:

These oil and natural gas resources have been recently discovered in the self-declared exclusive economic zone of Israel, but took millions of years to accumulate under the sea and the ground in the areas in which they have been found. The fact that, before 1948, Palestinians owned most of the total land mass of historic Palestine raises the question of whether they have the right to claim a share in these reserves, which were under land they owned before 1948… There is a need for further economic and legal studies to ascertain the Palestinian share in historic and shared oil and gas resources.

(-pg. 30, emphasis added)

Gone are the strident proclamations of Palestinian ownership, and in their place are modest pleas for sharing and fairness. The Secretariat also makes it clear that they are describing a limited subset of the Levant Basin’s resources here, naming the 38 trillion cubic feet of Israeli offshore gas reserves and some additional shale oil reserves specifically as the resources described above. Whether or not the reader believes these reserves rightfully belong to Palestine, it should be clear that they have nothing to do with the ongoing war. Israel, after all, already has them.

It is only then, after all the discussion and argument described above, that the $524 billion figure appears in the document’s body. Unlike the legions of social media acolytes claiming to use it as a source, zero effort is made by the report to assert that it is located in or exclusively belongs to Palestine. That number is described as “[the] total… to distribute and share among the different parties in the Levant Basin province,” (pg. 30, emphasis added) among whom they explicitly include Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Occupied Palestine. (pg. 28) This text is present in identical form in the report’s executive summary, so even those with little devotion to reading should know this.

On this basis alone, anyone citing this source as proof that Palestine has $524 billion in energy resources should be dismissed out of hand. They are either illiterate or a liar. The UNCTAD Report is unambiguous in its argument: some resources in the land occupied by Israel since 1967 belong exclusively to Palestinians; some resources that exist in the land owned by Palestinians before 1948 should be shared between Israel and Palestine in some unspecified amount; and some should be shared among everyone in the region. It is only the final category to which the $524 billion figure can be applied, not the first as many have argued.

Exploring the Bounty of Occupied Palestine

After reviewing the 2019 UNCTAD report, it is clear that the viral claims surrounding Palestinian oil reserves are nonsense. It could, however, be argued that this doesn’t change the truth of the narrative. Perhaps those people were wrong on certain specific facts or made an honest mistake in misreading the source, sure, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re wrong in the broadest sense. After all, the document does say Gaza and the West Bank have energy resources that Israel is stealing. Perhaps those are the cause of Israel’s wars and settlements.

The rest of this article will thoroughly disabuse any reader of this notion.

When considering the resources of Occupied Palestine, the UNCTAD report makes an interesting decision that causes questions to arise. It places tremendous emphasis on and conducts a substantial analysis of the Gaza Marine deposit but relatively little on the Meged oil field. This seems odd. The Gaza Marine deposits are, by their figures, only worth about $5 billion, as opposed to the $99 billion attributed to the Meged field. It’s not as if the theft of the Gazan gas is positioned as more morally outrageous. Nor is it any more illegal, if indeed most of the Meged field lies under the West Bank as the report claims. This merits further examination.

First, the importance of the Gaza Marine deposit must be clarified. As the UNCTAD Secretariat put it, “the Palestinian people have been denied the benefits of using [this gas] to finance socioeconomic development and meet their need for energy” (pg. 22-3). The Gaza Marine deposit is, in this telling, important not just for the money but the energy it might’ve provided. Factoring in development costs the report suggests there are potentially $4.6 billion worth of gas there, but the impact could have gone beyond the dollar sign. Gas from Gaza Marine could have lessened the Strip’s dependence on external fuel and electricity. After all, Gaza’s primary power stations were originally designed to work with natural gas and not the heavy fuel oil they mainly use.

There would also be tangible benefits to Gaza’s economy. That economy, such as it exists, has largely evaporated since Israel imposed the blockade in 2006-7. Other than deeply imperiled farming and smuggling, the Strip’s only real economic sector is construction. None of those are reliable sources of income. The fortunes of smuggling wax and wane based on Egypt’s volatile politics, and the construction sector is totally reliant on imported materials, which makes it vulnerable to any obstruction in imports Israel might impose. Given the deals that were on the table, however, gas from Gaza Marine could have been a reliable revenue stream. Even if its value is smaller in dollar terms, natural gas could have made an outsized impact in Gaza.

That it was more important than the Meged is not obvious upon immediate review, though. The Meged oil field certainly looks more promising on paper. A total value of $4.6 billion is cute and all, but the Meged’s ~1.5 billion barrels of oil constitute the bulk of the monetary value UNCTAD calculated for reserves in the occupied Palestinian territory. The Secretariat calculated that at then-current prices of $65 per barrel of oil, the reserves in the Meged were worth over $99 billion. Net production costs, which averaged about $23.50 per barrel, would have reduced this to a more modest $63 billion in profits. That would make the Meged field about 14 times more valuable than the Gaza Marine field in raw dollar terms. Admittedly these estimates are a bit meaningless given how volatile energy prices are, but in recent history they’ve usually skewed higher, not lower. Seeing as this field is worth a lot more money, it would seem to be the more obvious candidate for stolen resources.

Unfortunately, these valuation figures are somewhat chimeric. Crude oil is, economically speaking, not an undifferentiated commodity that can be treated as fully interchangeable with oil elsewhere. Different grades (chemical compositions) of crude typically have defined consumers who have the infrastructure set up to refine it, so acting as if the oil would magically find a profitable place for export is highly questionable. Crude is also not a commodity whose value can be assessed solely by back-of-a-napkin estimates of the total size of its reserves. The amount of oil that can be extracted from a field while still profiting is usually not the same size as the total estimated size of all the oil there. Production costs can also be, for one reason or another, much higher than “average” regional costs. All of this is worth noting because it turns out Meged’s economic viability is nearly nonexistent.

There is a famous Israeli joke that Moses spent 40 years wandering the desert in pursuit of the Promised Land before ending up in the only part of the Middle East without any oil. For a number of strongly religious Jews and Christians, the idea that the Holy Land is devoid of such a divine gift as oil has never sat well. The Meged field was developed by an Israeli company called Givot Olam, whose founder Tovia Luskin believed that the Torah contains a passage in the Book of Deuteronomy (33:15) wherein God promises the tribe of Joseph oil. In fact, the name of the oil field, “Meged,” literally means “bounty” in Hebrew. This refers to the Deuteronomy verse, which promises the tribe of Joseph the “bounty of perennial hills,” which is also where the company gets its name. Luskin’s religious influences aren’t just limited to textual references, either. Before he was willing to begin drilling, he sought out a rebbe living in New York who he believed to be the Messiah (The Lubavitcher rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson). It was only after the rebbe blessed his efforts and told him that he would find oil in the Holy Land in the early 90s that he proceeded.

Ordinarily, such a company would have a hard time finding investors, but Luskin's crew was an exception. Most of Givot Olam’s 14,000 investors are members of the Chabad, one of the largest and best-known Hasidic groups (a popular sect of ultra-Orthodox Judaism that got its start in Eastern Europe) in the world.

Israeli energy professionals, for their part, had been aware that there was oil in the region since the nationwide energy surveys conducted in the 1980s. But none of them considered the oil that they believed to be there economically viable to develop. They were proven right a number of times through the late 80s and early 90s as a number of true believers (many of them Evangelical Christians from the US) tried to develop the oil there and all ran out of money before discovering an economically extractable oil deposit. Luskin and his backers were merely the ones who happened to “succeed.” They scraped together the money (some of it initially from Luskin’s personal savings) and painstakingly enlisted outside investors to purchase, survey, and prospect the field. They drilled several wells looking for oil, and at the Meged-4 site in 2004 finally managed to find enough for it to make headlines as potentially extractable. At the time, Luskin confidently speculated that twenty percent of the billion barrels they’d discovered would be recoverable, enough to produce 20,000 barrels per day for almost 30 years. Experts doubted this estimate but believed the well might net a more conservative 20-50 million barrels.

In the end, however, they never even came close. Luskin and Givot Olam would ultimately drill eight wells, and all but two came up empty. Only one, Meged-5, would ever achieve commercial production, and during its full production period from 2011 to 2016 it would only produce 1 million barrels before “technical difficulties” forced it to shut down. Overall production appears to have peaked at about 800 barrels per day before rapidly declining to about 400 per day. It turned out that Israel’s oil experts had been right when they had told Luskin that “production there won’t be simple.” Declining production in 2014 and struggles to establish the Meged-6 well caused an investor revolt, which thwarted Luskin’s plans to raise capital for further drilling and forced him out of the company entirely. Luskin was also dogged by accusations that his continual announcements of oil discoveries (which he had done at every well ever drilled by Givot Olam) amounted to stock manipulation, which put his company under intense scrutiny by Israeli business authorities even after he left.

In 2016 Givot Olam faced a twofold blow when Meged-5 stopped producing and Meged-6 went dry. After spending a year temporizing to hide the scope of the problem and failing to resume production, Givot Olam was stripped of its right to operate the field by the Israeli government. So much for the bounty of perennial hills. All that effort only netted Luskin and his company something like $85 million in total after between $78 million and $84 million in development costs. There was some noise in 2019 about a revival, but it appears to have gone nowhere. As reported by Israeli business paper Globes in 2014, Givot Olam’s business model was essentially to use the profits of each well to finance further ones. When Meged-6 crapped out before production even began in earnest, the company’s Haredi investors basically demanded their money back. No wonder the business hasn’t gone anywhere since then. As of 2024 it appears to still exist but has lost its rights to extract oil in Israel (currently being appealed), and the company website seems not to have changed since late 2015.

It is unlikely that any competing developer could revive the field, either. Israeli geologist Boas Arnon told Haaretz at the time of the 2019 revival prospects that it might cost $30 million just to drill another well through the faults and 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) of limestone overlying the oil deposit. Givot Olam allegedly asked for much more than that, supposedly aiming to raise over $150 million. This was probably for a full-spectrum revival, including covering past losses, getting the legal rights back, and drilling multiple new wells. Any competing firm that had the bright idea to try and extract the field would likely face similar challenges. After all, Luskin only went to the Haredi community for financing after the energy sector brushed him off.

The 2019 UNCTAD report estimated that the Meged field could, under optimal conditions, produce about 530 barrels of oil per day. This is fairly close to the field’s real production figures, although on the high end. If one sets aside the fact that the company who owned the field was legally barred from operating it and that the only productive field had gone dry over 3 years ago, it could even be called a reasonable estimate. But even if production could be restarted — something that would cost tens of millions of dollars and take several years to set up — that kind of output would suffice merely to put Israel among titans of oil production like Georgia and Tajikistan.

The figures provided by UNCTAD about the size of the field also appear to have a limited factual basis. The Secretariat asserts that the field contains 1.5 billion barrels of oil, but this is a claim for which the authors could find no evidence in the geological literature. It, along with many other claims about the field — such as that its grade of crude is “world-class pure” and “worth $100 a barrel” — appear to come directly from Givot Olam’s PR department. The authors would suggest that such a statement coming from the source is does should be taken with a healthy grain of salt. 1.5 billion barrels is 50% higher than the billion barrels Luskin claimed to have found in 2004, and Givot Olam’s statements do not explain how they determined that figure. Their claims also came just two months before a 2010 presentation to their investors given by contracted geologist Nick Wright estimated that the whole field had about 950 million barrels of reserves based on the density of oil per sq km measured at their existing wells. He also noted that only about 10-20 million barrels of that was actually proven reserves at the time, i.e. had been physically confirmed to be present.

Even if the higher estimate was true it wouldn’t matter. The most conservative estimates of the field’s potential were much higher than the reality proved to be. While Nick Wright confidently told the press that the field could produce 600 million barrels, he also produced several models with more solid priors to estimate the profitability of extraction. Even his most conservative economic modeling predicted a daily oil output of 1400 barrels per day (almost double the real peak) and a total output of 3.5 million barrels (more than three times the real production figures). Whether the field has 1 billion or 1.5 billion barrels is irrelevant. Nobody can even get any of it.

When asked by the authors about the Meged oil field, Dr. Elai Rettig — an assistant professor of energy politics at Bar-Ilan University in Israel and senior researcher at BESA — was dismissive of the field’s relevance:

Various companies have looked for oil in the area and haven't found anything worth their time. The "Meged" fields have conducted 8 drillings in these area since the 1990s. Only two of them resulted in development of very small amounts of oil — around 400-600 barrels per day. In comparison, Israel consumes over 200k barrels per day. 400 barrels a day is enough to keep the drilling company afloat financially, but it's hardly worth considering on a national level.

It should be clear at this point why Gaza Marine was emphasized.

The Troubled History of Gaza Marine

Gaza Marine is the field to which most of the report’s time is dedicated. Its invocation as the cause of the recent conflict has also been the most enduring since it has the admittedly modest benefit of not being completely made up. The field is real, its exploitation has seemed very possible on more than one occasion, and it could have had real, tangible benefits for Palestine. And yet nothing has ever come of it.

To understand this gas field, its broken promises, and why there is no chance it has anything to do with the current conflict, its troubled history must be explored.

The story of Gaza Marine starts in 1995, when as part of the negotiations for the Oslo II Accords the Palestinian National Authority was granted sovereignty over the seas within 20 nautical miles of the Gaza Strip. A few years later, in 1999, the British energy concern BGG discovered a gas field covering an area 17-21 nautical miles offshore, which put about three-quarters of it in the PNA’s sovereign waters. In November of that year, the PNA signed a deal with BGG which gave them a 25-year contract for gas exploration in the area. As one does in the petrochemical industry, BGG went back to the field in 2000 and drilled two wells as a feasibility test to determine if the field was suitable for production. Results were good, with the gas proving to be of high quality. BGG’s engineers figured the size of the field at about 1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (28-32 billion cubic meters, depending on the source), so the company went back to Israel to get approval to drill production wells.

The same agreement under the Oslo II accords that had given the PNA control over their limited territorial waters also conditioned economic activity there on Israeli security approval, so BGG had to ask the Israeli government before moving forward. Despite the protests of Israel’s domestic energy sector — led by energy consortium Yam Thetis, who held ownership rights over directly competing gas fields of similar size — then-Prime Minister of Israel Ehud Barak granted BGG security permission for extraction rather than an Israeli concern. This symbolic recognition of the PNA’s authority was also accompanied by an Israeli allowance that extended the sovereign waters of Gaza out slightly to cover the whole gas field. This allowance was later legally confirmed by the Supreme Court of Israel, forever removing Gaza Marine from Israeli claims of sovereignty.

BGG drilled the first well, dubbed Gaza Marine-1, in July 2000 and the second, Marine-2, in November. Per the ‘99 agreement between the PNA and BGG, the latter would hold 90% of the shares until production started, which would take a few years. At that point, the PNA’s Palestinian Investment Fund (PIF) would get 40%, three-quarters of which would go to Consolidated Contractors Company, a Syrian/Lebanese construction firm. At the time, it was hoped that this development process would kickstart Palestinian economic growth and finally permit Palestine energy independence from Israel, which supplied something like 90% of its electricity.

Even this early in the process, however, cracks were showing. Palestine’s miniscule energy market, which had a total annual consumption of about 1 billion cubic feet (i.e. less than a tenth of a percent of the gas field), was incapable of providing the demand for economic extraction. This meant that Gaza Marine’s gas was intended primarily for export from the beginning. BGG was unwilling to develop the field without a compelling long-term customer, and in the atmosphere of peace and reconciliation that pervaded in June 2000 (when the negotiations began) that was hoped to be Israel. Israel, however, was hesitant. For one thing, they had a competing bid for a similar amount of gas from their own energy sector to extract the nearby Noa and Mari-B fields, which were together of a similar size to Gaza Marine. There was also a third competing bid from a joint Egyptian-Israeli venture that planned to sell imported Egyptian gas to Israel’s state-owned electrical company.

Then history leaped back to life and posed tough new political questions to the process. The implosion of the July 2000 Camp David Summit intended by the Clinton administration to resolve the “Palestinian question” sparked the Second Intifada even as the Gaza Marine wells were being drilled. The explosion of violence caused PM Barak to resign and triggered the election of a new Israeli PM, Ariel Sharon, who took a hardline stance against allowing the gas to be exploited and refused to allow BGG to develop the wells. Save for a brief period from mid-2002 to mid-2003, when international pressure from British PM Tony Blair forced him to be accommodating, Sharon’s veto blocked further development of Gaza Marine.

The Second Intifada lasted over four years, and by the time it was over in February 2005 Israel was out of Gaza, and PNA President Yasser Arafat was dead. The prolonged crisis had accelerated Israel’s erection of a massive border wall and led to them putting every inch of the border under surveillance, laying the foundations for the future blockade of Gaza. There was a brief moment of hope for a resumption of development when Sharon was defeated and replaced by relative moderate Ehud Olmert in January 2006. Olmert’s government worked to revive the deal briefly entertained by Sharon during his Palestinian thaw — one which would see Israel pay $4 billion per annum for 5 billion cubic feet of natural gas — when negotiations resumed in mid-2007, but once again the hand of history intervened.

The same month that saw Olmert secure Beit Aghion (the official residence of the Prime Minister of Israel) also saw new legislative elections in Gaza in which political newcomer Hamas swept the Fatah — formerly the dominant party of the PLO and the governing party of the PNA — out of power. This sparked an internal power struggle in the PNA that led rapidly to a severe political crisis. Hamas (who controlled the legislature) and the Fatah (who controlled the Presidency and security forces) quickly became locked in a civil war. By June 2007 Hamas had violently seized control of Gaza and the Fatah had done the same in the West Bank, creating two competing Palestinian governments. Israel, which considered Hamas a terrorist organization, swiftly imposed the long-threatened blockade. With Egyptian cooperation ensuring the border was virtually sealed save for two border checkpoints, Israel proceeded to exercise iron-fisted control on all movement in and out of Gaza and throttle critical imports of foodstuffs, medical equipment, and fuel.

Negotiations over Gaza Marine, meanwhile, floundered. One of the first things Hamas did upon coming to power was declare that they wanted to renegotiate their share of the gas, arguing that the previous deal had been worked out to benefit Israel and local elites but not the majority of Palestinians. They also, amusingly, allegedly declared that as a “Christian entity” the construction firm CCC could not “represent the interests of the Islamic community” in developing their natural resources and wanted them out, too. Israel, for its part, explored efforts to cut the PNA out of the gas development deal and work with BGG directly. Elements of their security forces (particularly Mossad Chief Meir Dagan) refused to work with Hamas, declaring that moving forward with the current deals would amount to Israel “financing terror against itself.” Eventually, Israel’s inconsistent policy and mounting security concerns caused negotiations to fall apart. BGG terminated the gas development project in December 2007 and closed its offices in Israel entirely a month later. (They did, however, retain their share of the Gaza Marine fields.)

One short year after BGG broke off negotiations with Israel, the first Gaza War erupted. This was a seismic shift in the position of Gaza and Hamas that nearly rivals the imposition of the blockade itself. It immediately provoked accusations that Israel was attempting to steal the Gaza Marine field, which didn’t seem quite so crazy at the time. For one, it’s essentially an open secret that Israel had been planning Operation CAST LEAD (their 2008-9 offensive into Gaza) for at least six months prior to the actual attack, during which time they were still negotiating with Hamas. They used this time to combine their “mosaic” of pre-existing Hamas targets with the plentiful information offered by their informants at every level of Hamas’s internal organization. They also attempted to reopen negotiations with BGG starting in June 2008, right about the same time that they began planning the operation. Israel’s nearby Mari-B gas field had entered production in 2003 and expanded its extraction operations to other small, nearby gas pockets, so it seemed entirely conceivable that such a subsea pipeline might be extended to Gaza Marine to take advantage of it.

The only problem for this reasonable narrative is that it didn’t happen. That’s a given when making political prognostications. Sometimes things that seem reasonable or possible from an external perspective aren’t so compelling to the actual decision makers. The lesson that Israel’s leaders appeared to draw from the collapse of negotiations with BGG wasn’t that they needed to secure Gaza’s gas (international law be damned!) but that they needed to diversify their gas supply. And they did.

In 2008, just as it seemed so possible that they were going to steal Gaza Marine, the first gas from Egypt flowed through Israeli pipelines. It was the result of a deal cut in May 2005, when Israel had selected the joint Israeli-Egyptian bid to sell imported gas to the IEC after Gaza Marine was taken out of consideration. The terms of the deal were that Israel was to import nearly 60 billion cubic feet per year for $2.5 billion. This was an incredible deal, one which gave Israel a robust gas supply at well below market prices and proved enormously beneficial. In conjunction with the gas flows from Mari-B and Yam Thetis’s other related fields it fulfilled Israel’s demand for natural gas, which at the time provided 20% of Israel’s electricity. When Egypt’s domestic political turn toward Islamism threatened that supply in 2009, Israel quickly moved to develop the newly discovered Tamar and Leviathan offshore gas fields. By the time the Morsi administration in Egypt successfully sunk the export deal in April 2012, the Tamar field was less than a year away from production.

Those offshore gas fields changed the game for Israel. Once an “energy island” reliant on far-flung imports of oil and coal from locales as distant as Australia, Israel has become largely self-sufficient in energy terms. The colossal Leviathan and Tamar gas fields — together possessed of more than 30 times as much gas as Gaza Marine — have formed the backbone of a domestic energy sector and caused Israel’s natural gas consumption to rise elevenfold from 2004 to 2019. Israel even managed to become an energy exporter, sending billions of cubic feet to Egypt for liquefaction and export each year in a true reversal of fortunes. By 2025, Israel will likely be off coal entirely. In short, rather than steal Gaza Marine Israel chose to render it irrelevant.

BGG quickly came to see Gaza Marine as an albatross around its neck. After Israel put Gaza under maritime blockade in 2009, which (among other things) restricted offshore activity to 3 nautical miles offshore (rather than the 20 permitted by the Oslo II Accords), nobody could even get to the Gaza Marine field. That 3-mile limit was not a theoretical line but a fiercely enforced reality. In the first six months of 2012 alone the Palestinian Center for Human Rights reported 92 attacks on Gazan fishermen by the Israeli navy for straying beyond this line. Even if Hamas and BGG had still wanted to develop the field at this point, Israel had nixed the entire project both legally and physically. BGG spent years trying to offload the field but failed to find any takers. In 2016 they were bought up by Royal Dutch Shell, and in 2018 they finally gave up entirely. The field’s new owners transferred their entire 90% stake back to the Palestinian Investment Fund, who now owned 100% of the field but were unable to exploit that fact. Gaza Marine looked to be deeper in limbo than ever.

That is, it was. On 18 June 2023, Israel finally gave approval for Gaza Marine to be developed for the benefit of Palestinians. While they continued to hold their last-say rights in reserve — that is, the right to nix the whole thing on security concerns — this was the biggest step toward the development of Gaza Marine since 2007. The key broker in this deal appears to have been Egypt, who intend for the gas produced to be exported there for liquefaction. Egypt’s hunger for gas is enormous, so this effectively guarantees a stable foreign market for the gas. Israel’s approval marks one of the key steps toward the development of Gaza Marine at last, only waiting on a Western partner to come in and provide the technical expertise. Admittedly the whole thing was provisional, with both the PNA and Hamas expressing skepticism about how serious this was. Still, the future looked bright.

Until 7 October 2023.

Unless something dramatic changes the current state of war between Israel and Hamas, Gaza Marine is likely done for the foreseeable future. From the beginning Israel’s decision to approve development was recognized as a grudging willingness to let some of the gas revenue flow to Hamas. Now that Israel’s claimed war goal against Gaza is the wholesale destruction of Hamas, it is difficult to see how tempers will cool enough for the field to be developed anytime soon.

Examining the history of Gaza Marine in this manner makes the UNCTAD Report’s coverage of it all the more baffling. Certainly, they can’t be faulted for being unable to predict the future, but in their telling the history of Gaza Marine and Israel’s energy sector basically stops in 2008. At the time of the report’s publication, almost all of the above information was known. Despite the fact that it was public knowledge that the Western investors and their critical technical expertise had cut and run, Israel had moved on, and the governing agency with whom the deals had been negotiated no longer even controlled Gaza, all the report has to say is:

In 2018, 18 years had passed since the drilling of Marine 1 and Marine 2. Since PNA has not been able to exploit these fields, the accumulated losses are in the billions of dollars. Accordingly, the Palestinian people have been denied the benefits of using this natural resource to finance socioeconomic development and meet their need for energy over this entire period, and counting.

-pg. 23

This is baffling. Gaza’s energy market was (and is) too small for the field to be profitable based solely on domestic demand, so no energy company would dare develop it without an exporter in mind. But nobody was buying. Who was going to finance and import from the field before 2023? Not Israel, surely. The report positions Gaza Marine’s failure of development squarely at the feet of Israel’s blockade, which makes little sense. The field was struggling to make it out of negotiations even before Hamas had taken power, and not just because of Israeli intransigence. Its development was clearly swamped by world-historical processes out of the control of its stakeholders, not derailed by scheming in Tel Aviv.

Even if that weren’t the case, the reality is Gaza Marine is simply not as important as those bringing it up believe it to be. However reasonable it may have arguably been in 2008, it is insane to suggest that Gaza Marine is causing a genocide in 2024. 1 trillion cubic feet is a fairly small field. Mari-B, a field of similar size (~25 billion cubic meters, or ~883 billion cubic feet) was literally pumped dry by Israel in ten years flat. That was the case over a decade ago when their gas consumption then was less than a tenth of what it is now. As Columbia University senior researcher Karen Young told L’Orient Today last November: “If productive, which it is not, Gaza Marine would produce about 2 percent of what is currently being produced from Tamar and Leviathan… Gaza Marine is not something Israel finds worth going to war over.”

Some Questions about the “UNCTAD Secretariat’s” Work

To this point in the article, the 2019 UNCTAD report has been treated as a basically credible source which is occasionally in err but whose perspective is essentially correct. It is time to reevaluate this. In reality, the UNCTAD report is very clearly not a well-researched resource crafted by appropriately sober and professional economists with sector expertise. It is an extremely dubious source based primarily on the work of open conspiracy theorists and whose author obviously lacked knowledge of the subject matter. It is difficult to prove bias on the effort of authors from a distance, but even if one employs Hanlon’s Razor it would still take a genuinely impressive degree of intellectual laziness and irresponsibility to produce this report. The sheer lack of professionalism in its researching and writing is not only a disgrace to the UN as an organization but genuinely embarrassing once the scope of it is made clear.

And all of these revelations start with one odd little citation.

When discussing the history of the Gaza Marine field in the aftermath of the 2008-9 First Gaza War, the report makes a curious claim. It asserts, bizarrely, that after the imposition of the naval blockade Gaza Marine was “in contravention of international law, de facto integrated into Israel’s offshore operations, which are contiguous to those of the Gaza Strip (map 2).” This is a startling claim. If true, Israel would be directly stealing from Palestine and extracting their gas. This is of particular relevance because the field that the provided map illustrates is the Mari-B field. If Gaza Marine’s gas had been sucked up by that, it would already be gone. Mari-B went dry in 2013. The citation provided for this claim is an article by one “M Chossudovsky” writing at something called “Global Research.”

Michel Chossudovsky, the author of the cited article, is a former economics professor at the University of Ottawa in Canada. He is also a notorious conspiracy theorist who has, among other things, argued in the past that America has lasers that can cause climate change, that COVID-19 was invented by the WHO to conquer the world, and, of course, that 9/11 was a false-flag attack orchestrated by the CIA. He volunteered as a character witness in the defense of Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic when he was on trial for genocide. He is also the founder and primary editor of Global Research, which published his work. When he was referenced by name in a US State Department report describing him as a Russian disinformation asset, he “declined to speak about how globalresearch.ca functions and whether it is aligned with Moscow or any other government” because it would “not be appropriate.” (A classically unsuspicious thing to say in response to such an accusation instead of “no.”)

He is also the single most cited author in the 2019 UNCTAD report other than UNCTAD itself, with no less than 11 unique citations in an article with 95 in total. Two of his articles are cited at great length, one originally from 2006 and another originally from 2018. With the disclaimer that Chossudovsky has the extremely irritating habit of going back and editing his articles repeatedly, even as recently as 24 April 2024, the content contained therein is extremely alarming. It appears that his 2006 article is primarily devoted to asserting that Israel is going to annex Lebanon and Syria in cooperation with Turkey at the behest of Washington in order to clear the way for an oil pipeline to Europe and to seize water resources. His 2018 article, meanwhile, claims that Israel has been engaged in a long-running plan to steal Palestine’s gas resources and would integrate Gaza Marine with its own installations if the Gazan coastline were militarized. But even Chossudovsky never directly claims that this is the case, he just says that Israel would do it if they could. The claim that they actually did is unique to the 2019 UNCTAD report.

This is so alarming it defies easy description. One of the most insane men in the world is a keystone source for a report from the United Nations. Furthermore, while citing him that report went even further in its claims than he did! This immediately, to be frank, throws every single other thing said by the 2019 UNCTAD report into question. It cites crazy people and doesn’t even do so correctly. In the interest of limited time, only the report’s claims about energy will be interrogated, but the authors encourage those interested to check the report’s other chapters.

All of this begs a single, blaring question: how in God's name did such a man as Dr. Michel Chossudovsky end up being the single most cited author in an official UNCTAD report?

It is at this juncture that the true author of the UNCTAD report must be discussed.

Strictly speaking, the report does not claim any specific author. It purports to be written by the “UNCTAD Secretariat,” which essentially amounts to claiming the report was authored by UNCTAD itself. But in addition to providing a disclaimer that the report’s findings are “those of the author” and not the UN, it also claims that it was “drawing on a study prepared for UNCTAD by Mr. Atif Kubursi, Professor Emeritus of Economics, McMaster University, Ontario, Canada.” It is the view of these authors that, whatever the report itself may say, Dr. Kubursi is almost certainly its primary or even sole author. It is almost impossible to believe that as many mistakes and distortions as the report promulgated could otherwise be published.

Proving such a claim is, of course, virtually impossible. The report was published nearly five years ago and was done behind closed doors. Definitive evidence is not likely to come. There is, however, one person who has been putting his finger on the scale with regard to this matter: Dr. Kubursi himself. When interviewed by Atmos, a digital magazine covering climate issues, Dr. Kubursi is identified as the author of the 2019 report. As Atmos themselves put it:

“The rules about exploiting shared, common resources are not very well defined,” said Kubursi, author of the 2019 U.N. report. “Therefore, it comes a bit of a tangle of issues, and who gets what could easily be who has the louder gun and the bigger plane.”

It’s difficult to see where they could have gotten this notion save for from Kubursi himself, although that’s hardly definitive. His name is literally on the report, after all. The rhetorical alignment between the report and Kubursi is also illuminating, but the good doctor himself never actually makes the claim. At least, not to Atmos.

The final piece of the puzzle with regard to Dr. Kubursi recalls the original question about his competency: why did he cite Chossudovsky in a UN report? The answer appears to be that Kubursi himself shares those beliefs, at least according to an op-ed he wrote in Canadian 9/11 “truther” outlet The International Center for 9/11 Justice. This op-ed is, to be frank, incredible. Kubursi covers every single base that the myth-mongers do, including the side stuff about the Ben Gurion canal and the New Silk Road brought up by Medhurst. If the op-ed weren’t dated 11 January 2024, it would be very tempting to label it the single origin of the myth for how comprehensive it is. In a footnote attached to the section title of the report’s third section, Kubursi states that its content is “taken from Atif Kubursi. 2019. “Occupation and the Economic Cost of the Unrealized Palestinian Oil and Gas Potential.” Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.” If that’s not enough, a video panel that included Dr. Kubursi from the same site advertised his work “in United Nations capacity” as a demonstration of his academic credibility.

Admittedly, the “Kubursi prepared it UNCTAD employed it” theory is not entirely dead based solely on this information. The title with which Kubursi refers to this report does not appear to exist anywhere else on the internet, so it’s possible that it was an unpublished internal UNCTAD report used to create the public one. His introduction in the video panel is also quite vague and, as the host said, time-constrained. The thing that makes accepting this story difficult is the second count against Dr. Kubursi, which is his exceeding intellectual laziness and plagiarism.

Both the third section of his article and the preceding section (at least) are riddled with plagiarism. The primary source of the plagiarism in the second section — the one that does not carry a disclaimer of being taken from another source — is the published version of the 2019 UNCTAD report.

Regardless of whether he wrote it or it was merely written using his work, it is extremely doubtful that Kubursi holds the copyright for the report. The report itself makes it very clear that it isn’t in the public domain and has a copyright held by United Nations Publications in New York. At best this is probably self-plagiarism. Writers being held to professional standards are always supposed to cite their sources, and just providing a footnote doesn’t make it okay to verbatim replicate material in the source without actually quoting it. Attentive readers will also note that while the paragraphs from the op-ed are relatively linear, the copied portions of the UNCTAD report come from all over the place. It is unimaginable that this could occur by accident. It does not, however, directly prove that Kubursi wrote the report. Only if, say, the copying of the UNCTAD report were to continue into the section where he does admit to taking from his own past work, would this narrative hold water. After all, he would be laying claim to work that is directly in the public UNCTAD report.

Unsurprisingly, the verbatim copying of the UNCTAD report continues in the section in which he claims to be drawing on his own work. The direct plagiarism goes on for several more paragraphs, with the only change being some slight rearrangement of the order they are in but not in content. This at the very least indicates that Kubursi is extremely lazy. His op-ed is extremely long and barring further plagiarism discoveries (which seem likely) it clearly constituted a great deal of writing. Taking a shortcut and just copying oneself instead of rewriting the material to flow better with the new material is just lazy. As those familiar with plagiarism likely know, however, it is never just “a one-time thing.” Attentive readers may have noticed that there is a large gap between the first plagiarized segment and the second. This is not because Dr. Kubursi stopped plagiarizing, but because the target of the plagiarism changed.

Dr. Ana-is Antresyan is a Geneva-based researcher who wrote an extremely detailed history of the efforts at developing Gaza Marine to the point of the article’s publication in 2013 in the Journal of Palestinian Studies. She is the second most-cited source in the 2019 UNCTAD report after Chossudovsky himself, and her article was one of the keystone sources in the writing of this one. In Kubursi’s footnotes, he claims that the portion of his op-ed beginning with the second paragraph of his third section— that part allegedly “taken from” his own report —is “[in] good part… extensively based on [her] article.”

“Extensively based on” it, indeed.

Once again, this plagiarism goes on for a staggeringly long time. Of the 3,500 or so words comprising the two sections dissected, only about 630 (~18%) appear to be unique to Kubursi’s op-ed. Of the 35 body paragraphs, only three appear to be unique content in their entirety. This figure includes points where Kubursi provided a new citation, referenced the same source in a different way, replaced paraphrase with direct quotation, and changed things to the current date. The copyright status of Dr. Antreasyan’s work is unclear, but it is not impossible that the copyright is held by her and that she gave Kubursi permission to do this. Even if that were the case and no plagiarism had been committed here, it reveals a genuinely impressive degree of laziness. Kubursi copies her text, replicates her citations, and then cites her only once.

Providing further evidence that Kubursi’s op-ed and the report share an author, the report itself pulls a similar trick. Clarifying in its section on Gaza Marine that its content is a “summary of some of the main points in [her] paper,” it proceeds to almost totally replicate Antresyan’s paper, too, albeit in a manner slightly less spectacular. The plagiarism is merely slightly better arranged.

This copying, predictably, occupies the rest of the section “summarizing” Antresyan’s work. While obviously less flagrant than the plagiarism in Kubursi’s op-ed, the amount of text virtually unchanged and rearranged to hide the extent of the similarity is disturbing.

The rest of Kubursi’s sourcing reveals a similarly intellectually lazy approach. Tied for third place in the number of times they are cited as a source by the report are Kubursi himself and Wikipedia. The good doctor cites himself on the state of the Palestinian economy several times, although these citations are at least for very specific claims. The Wikipedia citations, however, verge on unforgivable. In general, if one wants to use information they found on Wikipedia they should look at and make use of the source that Wikipedia used to find that information, not cite the website itself. But for common-knowledge, low-stakes citations it wouldn’t be the end of the world to use Wikipedia. That is not, however, the way Kubursi uses them. In fact, many of the report’s most surprising claims have Wikipedia citations, including the inflated figure for the size of the Meged oil field’s reserves, the dubious claims about Israeli shale oil reserves, and his figures for the cost of production of a barrel of shale oil. It seems that rather than review the literature, Dr. Kubursi chose to use a shortcut for information with which he was unfamiliar.

In fact, this behavior seems like a depressingly compelling explanation for the structure of the report itself. As noted previously, significantly more focus is placed on Gaza Marine — the least valuable of all the resource deposits mentioned in the report — than on everything else. Dr. Kubursi’s demonstrated laziness could provide a solid explanation for this. After all, not all of the resources discussed have a singular figure who synthesized the whole story like that. It takes much more research (at least for these authors) to piece together the story of things like the Meged field or Israel’s shale oil reserves in the same way. The 2019 UNCTAD report does not verbatim replicate the text of its sources the way Kubursi does, but it places the same degree of emphasis on the varying sources of information.

Enough said about the man himself. Whether he was malicious or simply unprofessional has no bearing on the factual inaccuracies in the report itself. Succinctly put, they are as follows: the report wildly exaggerates the size of energy resource deposits in the Levant Basin, employs dishonest methods in calculating their value, and consistently neglects to mention more recent work that supersedes or clarifies its own sources.

As has already been discussed, the figures provided by the report for the size of the Meged oil field are not correct. While it is suspicious that Kubursi insists that the incorrect figure of 1.525 billion barrels of oil are of “proven” reserves, this error is not much evidence by itself. It’s entirely possible that Kubursi could have taken the company’s figures at face value and not looked deeper. After all, he clearly either doesn't know or doesn't care what the term “proven reserves” means. In general circumstances, the company performing extraction would be the best source on the size of the reserves there. Givot Olam just happens to be extremely unreliable. But that is not the only exaggeration in size.

The report provides an inflated figure for the size of the Gaza Marine field as well, at 1.4 trillion cubic feet (~40 billion cubic meters). The available figures in the actual geological literature (and from BG itself) are between 28 and 32 billion cubic meters or between 990 billion and 1.1 trillion cubic feet. The figure given for the size of the field by Dr. Antreasyan — Kubursi’s second favorite author — is 1 trillion cubic feet. The actual source for the enlarged figure of 1.4 trillion cubic feet appears to be an Arabic-language Wikipedia clone page which doesn’t provide a source and Chossudovsky again. Although Chossudovsky and the Al-Monitor article which cites the Arabic Wiki page claim that the 1.4 trillion cubic feet figure is from BG, the Wiki page itself claims that the figure comes from Consolidated Contractors, who would have no idea how much is at the field. There is no situation in which a construction company would have a better handle on how much gas there was than an energy concern. Chossudovsky, for his part, defends the figure by suggesting that the publicly available figures from BG are on the low end, which makes no sense. Why would a business interested in selling its gas underestimate how much it had?

Even if Kubursi’s pricing and valuation methodology is considered to be correct, these exaggerations cause him to overstate the value of Gaza Marine by $2.08 billion (an inflation of 40%) and of the Meged field by at least $23.87 billion (an inflation of 62%). The fact that Kubursi chose to use a higher figure not just for the Meged field but for Gaza Marine as well makes it look even more suspicious. He chose to use that figure based on dubious evidence even though his own academic source said otherwise. But these are only the resources ascribed to Occupied Palestine. He engages in similar exaggeration of the resources of Israel and the Levant Basin.

The report talks about three main energy nodes in Israel: the offshore natural gas fields, a few million barrels of conventional oil, and shale oil. The reserves for Israel’s offshore natural gas fields and conventional oil are roughly accurate, but Kubursi makes a number of staggering claims about shale oil in Israel. It’s common knowledge that there is a large amount of shale oil — a type of unconventional oil reserve extractable only with hydraulic fracturing/fracking — in Israel. Kubursi cites the well-known figure of 300 billion tonnes of shale oil, a figure derived from the work of Tsevi Minster of Israel’s Geological Survey. (Although Kubursi cites Wikipedia, of course.) Using a figure of 6 gallons of oil per tonne from a paper on shale oil geochemistry, Kubursi calculates that this means Israel has 43 billion barrels of economically extractable shale oil worth $653 billion. This is further evidence that most of the advocates of the gaseous genocide myth never bothered to read the report, or else they would certainly have leaped at the opportunity to increase the $524 billion figure to a $1.2 trillion one.

To be blunt, these figures are ridiculous. While it is true that Israel has approximately 300 billion tonnes’ worth of shale oil formations, as Minster’s report notes only a tiny fraction of that could actually be extracted. Minster estimates that perhaps 1-2 billion tonnes of that could actually be mined. That would, using the figures for cost and valuation provided by the report, shrink the total value of the oil to perhaps $3 billion.

But those are incorrect as well. Kubursi appears not to even have read the geochemistry paper by E. Ekinci that he cites, which notes that 6 gallons per tonne is the bare minimum grade of shale oil that can be refined with present refining techniques. There is no good reason to have done this, and he doesn’t explain it as being a bare minimum figure. He makes use of it with zero explanation. Minster’s report notes that the economically extractable portion of the shale oil formations in Israel has an average oil yield of 20 gallons per tonne, for a total valuation of perhaps $11 billion. This means that Kubursi provided a figure that was about 60 times larger than the real one, assuming that his shale oil pricing was correct. Given Kubursi’s established tendency toward laziness, this genuinely begs the question of whether or not he read beyond the paper’s first page. All that would have been required for him to produce the correct (or at least more correct) figures would have been to read his own sources.

The report’s famous $524 billion figure is also completely imaginary. Kubursi positions it as “new discoveries in the Levant Basin,” but this is a lie. His source is a USGS survey from 2010 which provides mathematical calculations that estimate the amount of oil and gas that lie in undiscovered reserves in the region. Undiscovered reserves are a concept in energy studies that rely on existing knowledge of geology to estimate which geological bodies are likely to contain energy reserves. This begs the question of how reliable undiscovered reserves are as a means of calculating the amount of money one might share regionally, as Kubursi does. Dr. James Speight, a British chemist, geologist, and energy expert who is also a specialist in oil and gas reserves, had the following to say on “undiscovered energy reserves:”

…so-called undiscovered reserves… are little more than figments of the imagination! The terms undiscovered reserves or undiscovered resources should be used with caution, especially when applied as a means of estimating reserves of crude oil reserves. The data are very speculative and regarded by many energy scientists as having little value other than unbridled optimism.

-Handbook of Offshore Oil and Gas Operations, pg. 34. Emphasis in original.

This might be slightly too dismissive but accurately captures the rough picture of undiscovered reserves. Kubursi’s report provides the mean figures in the 2010 USGS report, but their calculated figures vary from that mean immensely. For example, the mean estimate is 1.7 billion barrels of oil, but the range of estimates varies from as little as 483 million barrels to 3.76 billion barrels. The same applies to natural gas: the mean estimate may be 122 trillion cubic feet, but the figures range between 50 trillion and 230 trillion. They are not figures that are meant to be taken at face value as real or proven reserves, and Dr. Kubursi’s portrayal of them in that fashion is extremely dishonest. In his correspondence with the authors, Dr. Rettig remarked that: